In vitro test guides follow-up studies

Underlying the appeal of personalized medicine is the link between in vitro and in vivo testing. The hope is that laboratory studies run on samples of body fluids will spot the earliest signs of disease, providing physicians with guidance on what to look for and where with imaging modalities.

Underlying the appeal of personalized medicine is the link between in vitro and in vivo testing. The hope is that laboratory studies run on samples of body fluids will spot the earliest signs of disease, providing physicians with guidance on what to look for and where with imaging modalities.

This hope is exemplified by a test designed to detect the spread of breast cancer. The in vitro diagnostic developed by a German biotech company, AdnaGen, appears able to identify the metastasis of breast cancer at a very early stage, according to research presented this week at the Molecular Diagnostics in Cancer Therapeutic Development meeting in Chicago.

The company's diagnostic tool can identify one malignant cell in a 5 mL blood sample with a specificity of 97%, according to Winfried H. Albert, Ph.D., chief scientific officer at AdnaGen.

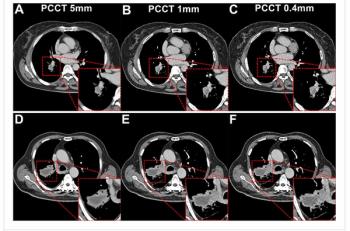

"We have seen cases where our test was positive and there was still no clinical evidence," he said. "But after a careful second look with a CT scan, small metastatic lesions have been detected."

The breast cancer assay is available in Europe, but the company is awaiting the results of a clinical trial under way at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston before applying for FDA approval to market the test in the U.S.

Secondary tumors, caused by spreading malignant cells, are the primary cause of cancer death. Early detection of metastatic spread is therefore crucial to a patient's prognosis. As a biomarker for breast cancer metastasis, cancer cells circulating in the blood have not been easy to detect and analyze because they represent a "needle in the haystack" among the millions of cells in the bloodstream, Albert said. The in vitro test developed by AdnaGen, however, picks out just that needle.

To produce its diagnostic tool, AdnaGen links antibodies specific to the cancer to magnetic particles. When exposed to a blood sample, the magnetic antibody binds with tumor cells possessing the target antigens. A magnetic particle concentrator then removes the cells for analysis.

In addition to helping physicians home in on the cancer with in vivo tools, such as CT, the in vitro test promises to help in the other aspect commonly associated with personalized medicine: fine-tuning the treatment regimen. Using this technology, AdnaGen discovered that the genetic signatures of the breast cancer and its metastases may differ, with the circulating tumor cells reflecting the gene expression profile of the metastases.

When a metastasis has been diagnosed, treatments "usually have been chosen according to the features of the primary tumor, neglecting the fact that a metastasis can differ from them considerably," Albert said.

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.