Urologist provides insight on advances in prostate imaging

An unusual eulogy delivered at ECR came from a urologist during a prostate cancer imaging session. The topic focused on a physical test that men have come to know, if not exactly love.

An unusual eulogy delivered at ECR came from a urologist during a prostate cancer imaging session. The topic focused on a physical test that men have come to know, if not exactly love.

"The finger is dead," said Prof. Bob Djavan of the University of Vienna.

The announcement referring to the digital rectal exam sent peals of laughter rippling around the hall.

"We still do the digital rectal exam because patients like it [laughter], but we don't need the finger any more because now we have PSA," he said.

From the urologist's viewpoint, imaging of the prostate is lagging far behind real-world needs, Djavan said. His key message was that the value of imaging in the prostate has been underestimated.

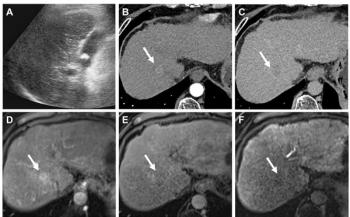

So far, prostate imaging has found a modest home in oncology, where CT is relied upon, perhaps unnecessarily, for planning radiation treatment.

The perception in urology is that imaging is of little use in prostate cancer. Clinical trials have focused on patients at low risk for aggressive cancer (new or recurrent), rather than those who are at high risk for a poor prognosis. This does radiology an injustice when it comes to evaluating prostate cancer imaging, Djavan said.

The disease is slow to kill, yet the PSA test enables early detection, which can give rise to treatment for cancer, regardless of the nature of the tumor. Ultrasound has proven helpful in changing the way prostate biopsies are performed, he said. And thanks to the study, ultrasound makes it possible to detect more cancers.

But that advantage represents a double-edged sword. The value of detecting all cancers early with ultrasound is questionable. Urologists order too much treatment, and radiation oncologists are sometimes too keen to irradiate.

"Radiation oncologists would irradiate a pimple," Djavan said.

Identification of the most aggressive cancers is vital, he said. About one-third of men will experience recurrence after surgical treatment within seven years.

Patients at higher risk stand to benefit more from early detection, possibly through imaging. Yet too often, clinical trials are diluted by low-risk patients, making it appear that imaging has less of a role of play.

"If you include this group of low-risk patients, you dilute your study with low sensitivity and low specificity patients, and that will kill your technology," Djavan said. "The trend is toward finding high-risk patients. If you do that, you will have much better results with imaging."

Large trials have shown potential for reducing mortality with early detection of recurrence.

"We would be much better off if we had accurate tools for imaging to detect recurrence and treat those patients early," he said.

Djavan stressed the need for radiologists to combine and correlate imaging studies with clinical tests like PSA, which is the main tool for detecting recurrence. The Gleason score also plays a critical role in predicting likelihood of recurrence.

Prior to surgery, it would be very useful if imaging could show whether the patient has organ-confined disease. Some researchers are beginning to experiment with computer modeling that combines clinical tools with imaging to predict likelihood of cancer recurrence before the patient even gets on the operating table.

To combine imaging with clinical techniques successfully, radiologists should aim to work with urologists.

"Don't play your own game and don't be individuals. Help us treat people who need it and don't treat those who don't need it," he said.

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.