Second look at x-ray, CT exams could reduce diagnostic errors

Simple physician checklists, diagnostic decision-support systems, or second looks at medical imaging exams could help to reduce the estimated 40,000 to 80,000 hospital deaths in the U.S. from diagnostic errors.

Simple physician checklists, diagnostic decision-support systems, or second looks at medical imaging exams could help to reduce the estimated 40,000 to 80,000 hospital deaths in the U.S. from diagnostic errors.

Writing for the March 11 Journal of the American Medical Association, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine physicians Dr. David Newman-Toker and Dr. Peter Pronovost stressed that diagnostic errors deserve the same attention as drug-prescribing errors, wrong-site surgeries, and hospital-acquired infections.

Diagnostic misadventures represent a potentially much larger source of preventable health problems and deaths than many of the more popular targets of safety reform, they said. Tort claims for diagnostic errors -- defined as diagnoses that are missed, wrong, or delayed -- are nearly twice as common as claims for medication errors.

Blaming physicians for a lack of training or necessary skill to avoid errors has not helped to reduce misdiagnosis rates, said Newman-Toker, an assistant professor of neurology with credentials in otolaryngology, informatics, epidemiology, and health policy. He supports moving away from a model that chastises individuals to one that focuses on improving the medical system as a whole. The change could result in big payoffs for improved diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness.

"There is often a mismatch between who gets advanced diagnostic testing and who needs it, leading to worse outcomes and higher costs. Realigning resources with needs could improve outcomes at lower cost," he said.

For an example, Newman-Toker points to problems with emergency triage protocols that categorize patients with typically benign symptoms, such as isolated headache, as being at low risk, though such symptoms sometimes indicate dangerous conditions, such as hemorrhaging brain aneurysm.

A systematic fix that could decrease diagnostic errors might be a change in overall rules for the triage protocol to consider specific symptom details that distinguish between low-risk and high-risk types of headache, he said.

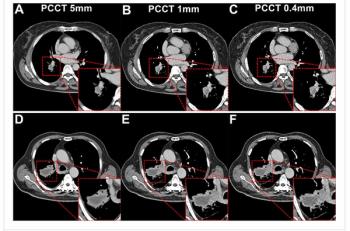

Newman-Toker and Pronovost, a professor of anesthesiology, critical care, and surgery, suggest that diagnostic errors may be reduced with checklists that help physicians remember critical diagnoses or diagnostic decision-support software that assists them in calculating the level of risk for individual patients. Health systems could further decrease diagnostic errors with time-tested low-tech tools such as independent second looks at x-rays and CT scans or rapid steering of patients with unusual symptoms to diagnostic experts.

"The first step in addressing diagnostic error problems is to shine a light on them so they are clearly visible," Pronovost said. "Then with wise investments, clinicians, researchers, and patients can discover how to prevent them."

For more information from the Diagnostic Imaging and SearchMedica archives:

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.