The Trouble with Ultrasound’s Pervasive Use by Non-Radiologists

Thanks to it being a safe, easy-to-use modality and the machines becoming increasingly smaller and more portable, clinicians ranging from trauma surgeons to cardiologists to anesthesiologists, are finding uses for ultrasound. But point-of-care ultrasound offers a trade-off between modality expertise and speed of diagnosis.

Use of ultrasound by non-radiologists has shot up in recent years, for procedures and for diagnostics. Thanks to it being a safe, easy-to-use modality and the machines becoming increasingly smaller and more portable, clinicians ranging from trauma surgeons to cardiologists to anesthesiologists, are

This is according to a recently published review article in the New England Journal of Medicine, “Point-of-Care Ultrasonography” (2011, 364:749-57), written by Christopher M. Moore, MD and Joshua Copel, MD, in conjunction with the November 2010 American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) Practice Forum on point-of-care use of ultrasound. At the forum, 45 organizations came together to discuss and develop specialty-specific performance and training guidelines for the use of ultrasound. The AIUM continues to work with these groups on guidelines.

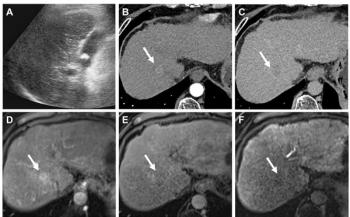

While its use is well-known in pregnancy, ultrasound is increasingly helpful in diverse specialties for both procedural guidance as well as diagnostic use. In procedures, ultrasound is used by clinicians to decrease complications and verify needle placement for anesthesia, biopsies, vascular access, thoracentesis, and abscess drainage. In terms of diagnostic use, doctors use it for focused exams of specific organs, trauma, or disease.

This recent article doesn’t uncover ground-breaking science, but it does “inform the medical community and lay people that this is an important modality, very pervasive,” said Nisenbaum.

Point-of-care ultrasound offers a trade-off between modality expertise and speed of diagnosis, according to Deborah Levine, MD, chair of the American College of Radiology (ACR) Ultrasound Commission and Professor of Radiology at Harvard Medical School. “Potentially it offers faster diagnosis, but not necessarily better diagnosis,” she said. “There’s a trade-off between knowing ultrasound and having the best equipment, and being the primary-care provider and using ultrasound.” She noted that radiologists have years of training in the modality, having studied proper use, the physics behind it, and differences in the various machines.

It’s great that ultrasound can offer more immediate results, Levine said, but those results only help if they’re accurate. “The threat of point-of-care ultrasound for patient care is if the machines aren’t good enough quality to answer the clinical question, if the anatomy isn’t understood, if artifacts aren’t understood, if anomalies are missed, and if there are false positive diagnoses that increase patient anxiety or add additional procedures,” she said.

No matter what specialty is using the modality, training is paramount, Nisenbaum and Levine said. In the early days of ultrasound, learning ultrasound was a matter of on-the-job training, said Levine. “Now ultrasound technologists have to go to school to learn about the machines, the anatomy, the physiology, and they have to take a test, so we know there’s a minimum standard for quality patient care.”

Not so for point-of-care ultrasonography.

“With point-of-care ultrasound, it’s like you’re taking a huge step backwards, and you’re back to on-the-job training,” she said, adding that many clinicians using it think on-the-job training is fine, because they are doing very focused exams. “But all the pitfalls are still there. If you don’t have a minimum standard of training, things can get lost with on-the-job training.”

She suggests four main categories for minimum training in ultrasound for patient care: training, competence, continuing medical education, and quality assurance. Figuring out who is setting that minimum standard, however, is difficult.

“Who is making sure people using ultrasound have the appropriate training, understanding and competence to do the procedure correctly, and who is monitoring the quality of the exams?”

For quality assurance, Levine wants the point-of-care ultrasound images and reports to be available for viewing by other clinicians. “You want to make sure that images taken can be seen by anyone outside of where they’re taken, that they don’t disappear,” she said.

In a hospital, any treating clinician can access a patient’s radiology images. “With a lot of point-of-care ultrasound,” said Levine, “storing images and having them be part of the medical record is not part of the culture, and perhaps the infrastructure is not there.”

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.