South Carolina radiologist defies ‘Rad Scare’

Radiologists should aggressively contest otherwise scientifically sound information on cardiac CT radiation risks that is taken out of context or blown out of proportion, fomenting unreasonable fears of medical imaging among patients.

Radiologists should aggressively contest otherwise scientifically sound information on cardiac CT radiation risks that is taken out of context or blown out of proportion, fomenting unreasonable fears of medical imaging among patients.

Dr. Joseph Schoepf addressed this issue during a cardiac imaging session Tuesday at the RSNA meeting. Schoepf is an associate professor of radiology at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

"We have been using radiation for the last century to diagnose disease, to steer patient management, and to reduce doubt in medical imaging. And we cannot allow and we cannot afford a public discussion of what we do to be all of a sudden overtaken by radiation fear, considering all the benefits that we provide our patients on a daily basis," he said.

Schoepf criticized mainstream media reports of a study published last year in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The JAMA paper concluded that patients undergoing cardiac CT scans had a one in 114 risk of developing cancer. The lay press stirred public concern with such statistics but overlooked that the figure was calculated using data extrapolated from Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb survivors.

The press also neglected to mention that the theoretical cardiac CT protocol included a 20-year-old woman scanned with a high dose, he said.

Schoepf challenged as well the conclusions of an editorial by Drs. Rita F. Redberg and Judith Walsh accompanying a study on cardiac CT published Nov. 27 in The New England Journal of Medicine. The note, a criticism of cardiac CT's cost-effectiveness, quoted evidence that cardiac imaging leads to unnecessary procedures and "bombards patients with radiation many orders of magnitude greater than that of traditional radiographs -- posing a risk that has never been studied in depth."

"We want to set the record straight and get a more realistic picture of what's actually going on in clinical practice," he said.

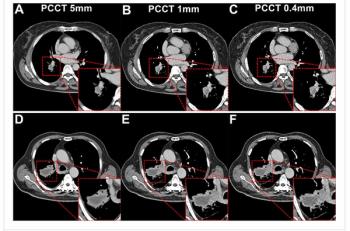

Schoepf presented findings of a study of 104 consecutive patients (64% males) with a median age of 59 who underwent cardiac CT on a 64-slice scanner. Researchers calculated organ dose using the ImPACT dosimetry spreadsheet. They calculated fatal and nonfatal radiation-induced cancer risk using the BEIR VII method and adjusted risk, taking into account patients' sex, age, and weight. The investigators found the average patient's risk of developing cancer was 0.12%, with a mortality risk of 0.1%, mostly from lung disease (85%).

Some radiologists feel uneasy even about the one in 1200 life-time risk of induced cancer in this patient population, however. Schoepf played down fears by pointing out no data directly link CT-based radiation with cancer. He also noted that the study followed a similar design as the JAMA paper by applying calculations to an actual clinical population. These calculations are filled with uncertainties, however, and physicians know that cardiovascular and coronary artery disease is a greater killer than cancer, Schoepf said.

"Let's keep in mind that we are radiologists. The use of radiation is in our name and that's what we do," he said. "If appropriately indicated, the theoretical risk from radiation is always outweighed by the real risk from complications or by missing the diagnosis."

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.