Report from ECR: Correct modality choice proves essential in head and neck trauma

CT and MRI have a vital part to play in cases of head and neck trauma, but it is important to know which modality to use under the clinical circumstances, according to speakers at Friday’s opening session of the minicourse on major trauma.

CT and MRI have a vital part to play in cases of head and neck trauma, but it is important to know which modality to use under the clinical circumstances, according to speakers at Friday's opening session of the minicourse on major trauma.

CT has high sensitivity for mass effects, ventricular configuration, bone injuries, and acute hemorrhage, and it is rapid, compatible with life-support equipment, and necessary for directing immediate neurosurgical intervention, said Dr. Ulrich Linsenmaier of the department of clinical radiology at Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich, Germany. But it cannot detect small nonhemorrhagic lesions and is insensitive for diffuse axonal injury (DAI), increased intracranial pressure, edema, and ischemia.

"The symptoms of head trauma can be masked by concomitant injuries, including blood loss, hypotension, and intubation," he said. "Presentation varies according to the injury. Some patients stabilize, but others deteriorate."

The incidence of head trauma is around 300 per 100,000 per year (0.3%) in the U.S. The mortality rate is about 25/100,000 (0.025%) in the U.S. and 9/100,000 (0.009%) in the EU. Common causes are traffic collisions, accidents at home and work, falls, and assaults.

Linsenmaier recommends follow-up CT in cases of confirmed patient deterioration and if the Glasgow Coma Score is not equal to 15 after 24 hours. Further scans are also necessary for detecting delayed hematoma, hypoxic lesions, and cerebral edema.

He noted that the primary effects of head trauma are penetrating injuries (missile or bomb fragments), epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma (SDH), cerebral contusion, subcortical injury, DAI, and acute, subacute, chronic, mixed, and traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage.

The secondary and vascular effects are intracranial herniation syndromes, traumatic cerebral edema, traumatic cerebral ischemia, brain death, traumatic intracranial/extracranial dissection, and traumatic carotid-cavernous fistula.

Initial assessment should be carried out in the emergency department immediately in cases of major trauma, polytrauma, and multiple trauma. Patients with single head trauma should be seen within 15 minutes of arrival at hospital. A CT scan must be performed immediately in patients with suspected major trauma, within one hour after trauma for those patients with risk factors I, and within eight hours after trauma for those with risk factors II.

MRI is sensitive for subacute or chronic lesions, atrophy, focal encephalomalacia, hydrocephalus, and chronic SDH. It is not currently indicated primarily for nonhemorrhagic lesions, DAI, vascular injuries, and dissections, Linsenmaier said.

Plain x-rays should be omitted in adults and are only of limited value for imaging of penetrating injuries and foreign bodies. They are also useful in children with suspected nonaccidental injury.

For further reading, he referred course attendees to the American College of Radiology's Appropriateness Criteria Head Trauma from 2007, the U.K. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence's Head Injury Guidelines from 2007, and Dr. Anne Osborn's book, Diagnostic Imaging: Brain (W.B. Saunders, 2004).

Later this month, he will speak at a conference in Munich called "Battlefield Healthcare 2009: From front line care through rehabilitation." A preconference focus day on March 24 will concentrate on imaging, and he will address the topic of mass casualty incidents.

In facial trauma, imaging provides information about the presence, location, and extent of fractures, as well as cranial nerve compromise and the involvement of the skull base and dura. It also has a role in the selection of treatment to stabilize facial anatomy and relieve or prevent complications, said Dr. Minerva Becker, a radiologist from Geneva University Hospital in Switzerland.

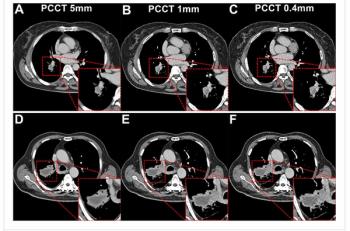

"In most cases of major facial trauma, CT is the most rapid examination that performs best," she said. "It provides a one-stop shop approach. Either you use whole-body CT protocol for polytraumatized patients, or you use more limited protocols for the brain and face."

For the face, she advocates taking thin slices with a collimation of 0.75 mm and then reconstructing them at 1.5 mm. It is important to look at the bone and soft-tissue window settings, and she makes increasing use of intravenous contrast media, particularly if she suspects the facial fracture extends to the skull base with possible additional vascular injuries.

"MR is used as a second-line approach when CT has been performed but some points remain unclear, such as the extent of vascular injuries, optic nerve lesions that cannot be identified on CT, and radiolucent foreign bodies," Becker said.

When speaking about maxillofacial trauma, she said it is vital to bear in mind that the energy applied to the viscerocranium is a product of the mass and the square velocity. Radiologists must differentiate between high- and low-impact zones. High-impact areas consist of bones that are relatively resistant to trauma, such as the supraorbital rim, frontal bone, and mandible. Low-impact zones include the zygoma and nasal bone, which fracture easily when minor force is applied to the facial skeleton.

"In as many as 50% of patients with major facial trauma, you have associated cervical spine, airways, vascular, or brain injuries. So you don't only have to image the face but also all the other related injuries that may be present," she said.

For more online information, visit Diagnostic Imaging's

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.