MRI enhances whole-body imaging

Provided cost-effectiveness issues can be resolved, whole-body imaging appears destined to enter everyday clinical practice as a comprehensive initial scanning method in oncology and other areas, according to an ECR presentation Friday.

Provided cost-effectiveness issues can be resolved, whole-body imaging appears destined to enter everyday clinical practice as a comprehensive initial scanning method in oncology and other areas, according to an ECR presentation Friday.

Whole-body imaging enables the acquisition of 3D high-resolution data sets of all organ systems in a single examination. A whole-body study can be performed in about one hour, potentially eliminating the need to call patients back on separate occasions for scans of various organs.

"It is important for general radiologists to see what is technically feasible now and what will be routine in the future. In oncology, cardiovascular disease, and emergency room cases, whole-body imaging will definitely become the diagnostic method of choice," said Dr. Heinz-Peter Schlemmer, an associate professor of radiology at Eberhard-Karls-University Hospital in Tübingen, Germany.

High-resolution whole-body MRI using multiple phased-array surface coils entered the commercial market in mid-2004, complementing whole-body spiral CT technology, which has been available for more than six years. Whole-body MR scanners have enhanced the appeal of the "one-stop-scanning" approach.

These MR systems are expensive, however, and typically available only in large hospitals and/or facilities that specialize in oncology. Whole-body studies require more time and effort to work up and read, but reimbursement does not reflect the additional workload. As positive clinical evidence mounts, and if cost-effectiveness can be proved, whole-body imaging could become much more widely used.

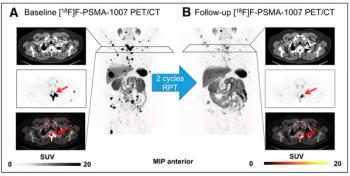

Whole-body techniques appear especially promising for rapid initial diagnosis of oncology patients to evaluate metastatic spread, Schlemmer said. The modality is increasingly being used for this purpose in combination with PET/CT. MRI offers better soft-tissue contrast than CT, and it also has advantages over PET. Although PET provides high sensitivity and specificity, it cannot detect metastases in the brain or small metastases, particularly in bone, lymph nodes, and organs such as the liver. MRI is useful in these organs, but its specificity is lower than that of PET. When MRI findings are nonspecific, further evaluation can be done with PET/CT to rule out metabolic activity.

"MRI allows us to detect all small lesions. Sometimes we see them, but we cannot detect whether they are metabolically active or not. We can now use all these modalities, fuse images into one image set, and then very comprehensively assess the spread of the disease. This will help us to improve diagnosis for oncology patients," he said.

Schlemmer and his colleagues at Tübingen recently put whole-body MRI to the test in a prospective study of more than 100 patients with various solid and hematological malignancies. The radiologists independently compared whole-body CT with whole-body MRI for detecting metastatic spread. In 42 patients with malignant melanoma, they found that whole-body MRI found lesions not seen on CT and could have changed therapeutic management in 20% of cases. Initial results were published in Investigative Radiology in February 2005.

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.