Hybrid PET/CT angiography strikes at clinical mainstream

Before considering revascularization procedures, surgeons want proof of ischemia. While catheter angiography has value in assessing lesions associated with coronary artery disease, it cannot assess the associated ischemia. PET imaging is increasingly being used to provide that information. With the rise of multislice CT angiography as a first-line test for patients with suspected CAD, researchers have set their sights on integrated PET/CT for combined acquisition of coronary anatomy and perfusion.

Before considering revascularization procedures, surgeons want proof of ischemia. While catheter angiography has value in assessing lesions associated with coronary artery disease, it cannot assess the associated ischemia. PET imaging is increasingly being used to provide that information. With the rise of multislice CT angiography as a first-line test for patients with suspected CAD, researchers have set their sights on integrated PET/CT for combined acquisition of coronary anatomy and perfusion.

"This is clearly an important marriage between nuclear imaging and CT," said Dr. Daniel S. Berman, director of nuclear cardiology and cardiac imaging at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. "Which patients will need both tests done in the same setting? We don't know the answer yet. What we do know is that there are patients who will need both."

The test still faces several challenges to widespread use: gaining reimbursement for the CTA portion, defining the appropriate patient population that would most benefit from the combined study, and developing more cost-effective radiotracers.

Some professional societies and organizations have dedicated themselves to securing reimbursement for CTA. The American Medical Association helped last year by issuing new CPT codes for coronary CTA, and a few clinicians across the country have convinced their local carriers to cover coronary CTA, but the technique remains a long way from standard. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services awaits published peer-reviewed literature that shows the combined tests are better and more cost-effective than existing techniques. Once Medicare grants coverage, third-party payers should follow suit.

"Third-party payers need to understand the proper role of CTA in risk stratification to diagnose patients," said Dr. Kevin L. Berger, director of PET/CT at Michigan State University.

At MSU, insurance companies will often approve payment for patients who would not benefit from the test, including those with stents, multiple prior interventions, or heavily calcified vessels. Conversely, they will not grant approval in younger patients who typically would not have high calcium burden and who would benefit from the test.

Right now, peer-reviewed evidence defining the appropriate patient population is scant. That is likely to change as more institutions adopt cardiac PET/CT, according to Dr. Marcelo F. Di Carli, a cardiologist and chief of nuclear medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

Two issues are at the forefront when new technology undergoes scrutiny: Will the test diagnose the disease, and will the diagnostic statement help guide an appropriate management decision? In the case of coronary disease, a normal CTA would exclude disease and lead to the appropriate management decision. An abnormal CTA, even one suspected to be obstructive, does not always correlate with a positive PET perfusion scan. In this scenario, only half of the patients would have evidence of ischemia on the PET study.

"If you rely solely on the CT information and disregard perfusion imaging, you will revascularize 50% of patients inappropriately," Di Carli said. "The negative predictive value of CT is extremely high, but the positive predictive value to identify patients in need of revascularization is fairly low."

Reconciling these two extremes leads to further questions. Will CT be done on everyone as a first-line test, followed up with perfusion imaging in those with an abnormal scan? Would that be the most cost-effective approach versus the current protocol, which is to perform the perfusion test, make the diagnosis, stratify the patient's risk, and make a management decision?

The cost-effectiveness of either approach depends greatly on the patient group, Di Carli said. The value of CTA for excluding disease in older symptomatic patients with a high probability of calcification, for example, is low compared with younger patients who are not likely to have calcium.

"We can't make a simplistic statement that this combined test will be equally applicable to all patients. We have to specify which population," he said.

CAN IT BE DONE?

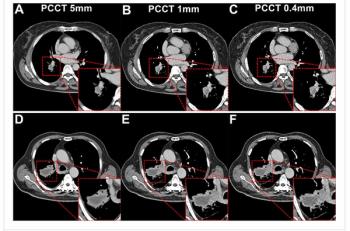

In one of the first published studies assessing the feasibility of integrated cardiac PET/CTA, Dr. Gustav von Schulthess's group at the University Hospital of Zurich found the technique not only feasible but accurate to visualize coronary anatomy and simultaneously assess the functional significance of lesion severity. These results came with a four-slice CT scanner. Led by Dr. Mehdi Namdar, the research team performed contrast-enhanced CTA and rest/adenosine-stress PET myocardial perfusion scanning with nitrogen-13 ammonia on 25 patients with CAD that had been documented by coronary angiography (J Nuc Med 2005;[46]:930-935).

The standard reference of PET perfusion plus conventional angiography identified 11 lesions with corresponding ischemia that qualified for revascularization. The 89 remaining coronary segments did not qualify for revascularization, as they contained either no stenosis and no ischemia or stenosis without ischemia. Integrated PET/ CTA correctly classified 82 of these 89 segments, indicating that an invasive diagnostic procedure could have been avoided with the noninvasive test, according to the study.

These results are promising but require further confirmation in larger trials. One such trial will launch early this year. The study of myocardial perfusion and coronary anatomy imaging roles in coronary artery disease, or SPARC, will enroll 3700 participants from 40 U.S. sites. Recruitment should be complete within 12 months, with two years of follow-up, according to Di Carli, the co-principal investigator along with Dr. Rory Hachamovitch, a cardiologist in the division of medicine at the University of Southern California.

Patients in SPARC will be randomized to one of four imaging arms: SPECT, PET perfusion with rubidium-82, integrated PET/CTA, and CTA alone. The main objective will be to evaluate conventional catheter and revascularization rates across different imaging arms and then compare outcomes, including myocardial infarction and death. Researchers will also compute the cost-effectiveness of each arm.

Such a trial will be welcomed by those in the field, Berger said. Now, no studies show that a combined PET/CTA scan holds an inherent benefit over conventional imaging. If a patient has a borderline SPECT or PET perfusion deficit, the CTA would help show which vessel it is. But many people could argue that the patient should go to the cath lab anyway.

Berger cited an indeterminate CTA as one scenario where the combined test makes sense, because the clinician cannot be sure if the stenosis is flow limiting. The patient might have a 60% stenosis in the left anterior descending artery, but the question of whether it is potentially causing ischemia and explains the patient's symptoms could remain unanswered. A negative PET perfusion exam would argue that the stenosis may not be significantly flow limiting. A positive perfusion deficit correlating to a CTA abnormality would cement the management decision.

"Until we refine the CTA techniques to be more accurate on borderline significant stenoses calls, there is a benefit to look at PET perfusion information," he said.

THREE PATIENT TYPES

CTA results in a patient with a positive perfusion scan will determine the state of the coronary arteries and, therefore, whether invasive treatment is necessary. In a patient with an equivocal perfusion scan, CTA should help clinicians come to an unequivocal diagnosis. The test in a patient with negative perfusion will show only whether that person has underlying risk factors. If the coronary arteries are heavily calcified, even though the result of perfusion is normal, the patient might require aggressive medical treatment for atherosclerosis.

Patients with equivocal perfusion findings are most likely to benefit from the combined study, said Dr. Vasken Dilsizian, a cardiologist and director of cardiac PET at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore. CTA in these cases will tell whether coronary artery stenosis is not present, meaning no treatment is necessary. It also could reveal patients who have high calcium scores or minor stenoses of less than 50%. These patients could pursue risk factor modifications such as aggressive lipid lowering and hypertension control and be followed with noninvasive studies.

Many practitioners-and, perhaps, insurance companies-might ask why patients with abnormal perfusion scans need CTA. Dilsizian cites two reasons. While functional abnormality may be present, it may not be accompanied by structural disease that is anatomically amenable to revascularization. Also, perfusion defects could be due to endothelial dysfunction, multivessel disease, or distal coronary artery disease.

SPECT VERSUS PET

Nuclear cardiology is moving away from SPECT and toward PET, which includes PET/CT, according to Dilsizian. Cardiologists may take baby steps, first acquiring SPECT/CT, but ultimately PET will win out.

PET has a superior attenuation correction compared with SPECT, and it quantitatively measures blood flow reserve, making it reproducible across patients. Conversely, SPECT approximates reserve, leaving more room for variability among readers.

Di Carli does not think PET will replace SPECT, mainly because patients can't exercise on PET and SPECT imaging will get better as CT for attenuation correction is incorporated. PET will, however, have a role for patients who are the most difficult to image with SPECT: the obese and those who are sicker and can't hold still. This group includes about 40% of patients, or four million people.

THE ULTIMATE TRACER

Much research is being invested into different cardiac PET radiotracers. Berger and colleagues are working with investigators to develop fluorine-based tracers with a half-life similar to FDG's two hours. Such a product could dramatically change the landscape of cardiac PET perfusion imaging, he said. A fluorine-based tracer would have the benefits of a regional cyclotron distribution network.

"If the right F-18-based radiotracer can be developed, it will solve many problems," he said. "N-13 ammonia has a short half-life (less than 10 minutes) and requires an onsite cyclotron. That's a huge problem for many PET institutions. We want to help develop techniques that are generalizable across the entire community."

A fluorine-based tracer would facilitate the dissemination of PET imaging, similar to what has been done with SPECT, Di Carli said. Rubidium is convenient, but it has a high fixed cost. Hospitals need to ensure they have the volume (about two patients per day) to offset the fixed cost.

Rubidium also has a half-life of less than two minutes, which can be problematic for gaining valuable dynamic data early in the scan. Rb-82 may not have the same spatial resolution and sensitivity as N-13, he said.

To date, only a handful of institutions have acquired a PET/CT scanner that is used for cardiac imaging. It's only a matter of time before more facilities purchase the machines, which will soon be available with 64-slice CT components. Clinicians then will wait for all the kinks to be ironed out, while the government and other third-party payers will await mature data on the efficacy of the combined tests. The sure bet is that cardiac PET/CT angiography is here to stay, Berman said. How the particulars play out regarding who goes to SPECT or who goes to PET, or who gets the CTA and who doesn't, will become clear soon.

Mr. Kaiser is news editor of Diagnostic Imaging.

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.