CT extends reach of forensic science

Autopsies have long been instrumental in documenting the cause of death from disease and crime. The procedure’s contribution to public welfare is beyond debate, but religious beliefs and family preferences have led to a decline in its use. Into this breach has stepped digital imaging in the form of CT, which lets forensic scientists investigate cases they would otherwise be prevented from working on.

Autopsies have long been instrumental in documenting the cause of death from disease and crime. The procedure's contribution to public welfare is beyond debate, but religious beliefs and family preferences have led to a decline in its use. Into this breach has stepped digital imaging in the form of CT, which lets forensic scientists investigate cases they would otherwise be prevented from working on.

A study to be published in the June issue of Radiology demonstrates the value of multislice CT in determining whether a person has drowned. Because CT is comparable to conventional autopsy in documenting the signs of drowning, it can serve as an adjunct procedure or a substitute for it in suspected cases, according to Dr. Angela D. Levy, chief of abdominal imaging at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, MD.

"More and more, advanced imaging tools such as multislice CT are being applied to forensic investigations," Levy said. "In the future, imaging in forensics may be just as important as imaging in clinical medicine."

Levy and colleagues performed total-body CT examinations on 28 consecutive male drowning victims and 12 men in a control group who were victims of sudden death from coronary artery disease. Following CT, routine autopsies were performed.

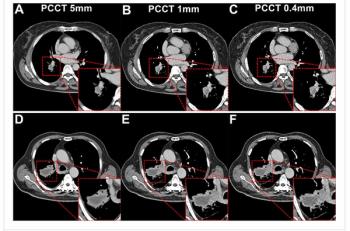

CT images were evaluated for the presence of fluid and sediment in the paranasal sinuses and airways, fluid in the ear, frothy fluid in the airways, obscured ground-glass appearance or thickening in the lungs, and swelling, fluid, or sediment in the stomach. Images were then compared with autopsy reports and photographs.

Multislice scans indicated that all (100%) of the drowning victims had fluid in the paranasal sinuses and ears, as well as ground-glass opacity in the lungs. Twenty-six (93%) had fluid in the subglottic trachea located below the vocal cords and main bronchi. Fourteen (50%) had sediment in the subglottic airways. Six (21%) had frothy fluid in the airways, and 25 (89%) had ground-glass opacity and thickening in the lungs. Twenty-five (89%) exhibited swelling of the stomach.

No members of the control group had frothy fluid or sediment in the airways or sinuses. Eleven (92%) had subglottic airway, tracheal, and bronchial fluid. All subjects exhibited collapsed stomachs.

Autopsy results were similar to those from CT for both groups.

"Airway froth and sediment can be demonstrated on CT and were specific to drowning, thereby replicating the findings seen at autopsy," Levy said.

Forensic scientists must determine whether drowning is the primary or secondary cause of death for a body found in water.

In cases of suspicious death, CT does not damage or destroy key forensic evidence as can happen during a conventional autopsy. MSCT can also be used in situations where autopsy may not be feasible or is prohibited by religious beliefs. When possible, however, CT would best be employed as an adjunct to routine autopsy, Levy said.

Based on this study, MSCT may provide support for the diagnosis of drowning when other causes of death have been excluded by a limited autopsy or external examination of the body. This type of virtual autopsy may also be useful as a pre-autopsy triage tool in mass casualty scenarios, the researchers said.

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.