- Diagnostic Imaging Vol 30 No 11

- Volume 30

- Issue 11

MR offers different option forpregnant appendicitis patients

Diagnosing pregnant women suspected of appendicitis is tricky business. Often the enlarged uterus will displace the appendix, making it hard to find with ultrasound.

Diagnosing pregnant women suspected of appendicitis is tricky business. Often the enlarged uterus will displace the appendix, making it hard to find with ultrasound. Using CT because the physician can't see the appendix on ultrasound raises the issue of fetal radiation exposure. These problems are pushing many physicians to MR.

Acute appendicitis occurs in approximately one in 1500 pregnancies, according to one study, and it is one of the leading indications for surgery in pregnancy (Mil Med 1999;164:671-674). Researchers in another study found that acute appendicitis complicates approximately one in 766 pregnancies (Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1999;78:758-762).

The standard of care for pregnant women suspected of appendicitis uses ultrasound first, then MR or CT, according to Dr. Marcia Javitt, section editor for women's imaging at the American Journal of Roentgenology and section head of body MRI at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, DC.

Dr. Gary Israel, an associate professor of diagnostic radiology and chief of body CT at Yale University, expects physicians eventually to forgo ultrasound and move directly to MR. Others share Israel's opinion. Dr. Ajay Singh, an assistant professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School, calls MRI of the appendix “the next frontier for widespread use,” citing concerns of radiation effects.

“When ultrasound findings are nondiagnostic or equivocal, MR imaging is the most appropriate modality for the evaluation of acute appendicitis in pregnant women,” Singh wrote in a study published in RadioGraphics (2007;27[5]:1419-1431).

“Although the high cost and restricted availability of MR imaging limit its utility in the emergency setting, the absence of ionizing radiation and the improved contrast resolution make MR imaging an appropriate modality for use in selected patients.”

Several studies suggest MR may be the best option when it comes to diagnosing pregnant women suspected of appendicitis.

Dr. Lodewijk P. Cobben from the radiology department at Medisch Centrum in Haaglanden, the Netherlands, and colleagues conclude in their 12-patient study that MRI is a valuable and safe technique for the evaluation of pregnant patients clinically suspected of having acute appendicitis (AJR 2004;183:671-675).

A study by Dr. Ivan Pedrosa, director of body MRI at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, and colleagues evaluated 51 pregnant women suspected of acute appendicitis using MRI (RadioGraphics 2007;27:721-753). Four patients had findings suspicious for appendicitis, and three were inconclusive. Overall sensitivity was 100%, and specificity was 93.6%.

“Radiologists should become familiar with the MR imaging technique, advantages, and unique features for evaluating patients with acute right lower quadrant pain,” Pedrosa said.

The researchers also found a 100% negative predictive value using MR, which is of great merit because it provides an effective means for ruling out a surgical diagnosis.

“Many patients can be spared radiation exposure from CT that may have been otherwise needed to determine patient treatment,” Pedrosa said.

WHY USE US OR CT AT ALL?

Physicians start off with ultrasound because it is widely available-most ERs have their own ultrasound system- and less time-consuming than MR and CT, said Dr. Shital Patel of the radiology department at Long Island College Hospital in Brooklyn. The test can be done quickly and at all times, including the middle of the night, making it the go-to choice when a suspected appendicitis case comes in.

Another benefit is cost. Ultrasound is five times less expensive than MR at Massachusetts General Hospital, according to Singh. A study by Dr. Sanjay Saini of the radiology department at Mass General found the technical costs of examinations with ultrasound, CT, and MRI in 2000 to be $50, $112, and $267, respectively (Radiology 2000;216[1]:269-272).

While ultrasound is significantly cheaper than MR or CT, its inability to visualize beyond air-containing bowel loops and difficulty in evaluating obese patients presents a problem in diagnosing pregnant women, Singh told Diagnostic Imaging.

Another disadvantage is that ultrasound is user-dependent, and that can make it difficult to identify appendicitis, Israel said.

When a physician cannot identify the appendix because it is displaced, he or she will often turn to CT because CT is extremely accurate. A recent study by Dr. Robert O.

Nathan, acting assistant professor of radiology at the University of Washington, Seattle, found CT of the appendix to have high sensitivity (94%), specificity (100%), positive predictive value (100%), negative predictive value (99%), and accuracy (99%) in a 100-patient study (AJR 2008;191:1102-1106).

Though CT is no doubt more accurate than ultrasound, however, it also exposes the fetus to radiation, making it a less desirable modality than MR.

“The recently increased awareness of and concern about radiation-related health risks warrant the adoption of a flexible approach to imaging in the emergency setting, particularly in pregnant and pediatric patients,” Singh said.

A fetus exposed to radiation between weeks two and 20 of embryonic development is most susceptible to the teratogenic effects of ionizing radiation, which include microcephaly, micropthalmia, mental retardation, growth restriction, behavioral defects, and cataracts (Reprod Toxicol 2005;20:323-329). The fetus is not considered at risk of teratogenesis, however, if irradiation does not exceed the threshold dose. This dose is estimated to range from 0.05 to 0.15 Gy (5 to 15 rad), according to one study (AJR 1996;167:1377-1379).

The acceptable radiation dose of a CT scan varies depending on gestational age and scanning parameters, but the estimated dose ranges from 0.024 Gy (2.4 rad) in the first trimester to 0.046 Gy (4.6 rad) in the third trimester, according to a study by Dr. Morie M. Chen, a clinical fellow in the radiology department at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues (Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:333-340).

“The radiation dose of pelvic CT is likely below the estimated threshold level for induction of congenital malformations,” Chen said.

The authors found the baseline risk of fatal childhood cancer to be five in 10,000 and the relative risk after exposure to 0.05 Gy (5 rads) to be 2.

“This relative risk may appear substantial, but it should be remembered that the baseline risk is very low, so the odds of dying of childhood cancer go from one in 2000 (baseline) to two in 2000 after 0.05 Gy (5 rads),” Chen said.

Even though the relative risk of fatal childhood cancer is low when using CT to diagnose appendicitis, it is still a factor that should be examined and the primary reason physicians are turning to MR.

“You can do a CT for appendicitis, but you have to examine the risks versus benefits of radiation exposure,” Javitt said. “You have to be convinced the indication is compelling.”

If the physician plans on using CT either because he or she is more comfortable with it or an MR machine is not available, it is important to minimize dose of the CT scan, Javitt said.

Chen pointed out that a low-dose CT protocol should be considered by changing parameters such as kilovoltage, milliamperes, pitch, and beam collimation. Lowering the dose too much results in image degradation, however, which renders the study nondiagnostic. Scanning only the required body area and making just one pass can reduce dose without affecting imaging quality.

In addition to minimizing dose, Javitt suggests providing the patient with access to a physicist to have the relative risk of radiation exposure explained and calculated.

“Relative risk is also theoretically different during the first versus second or third trimester,” she said. “There's a difference in sensitivity. Even in MR, we're concerned about the organs of the fetus because they're undergoing rapid change and development in a process called organogenesis.”

Javitt tries to avoid using radiation, going with ultrasound first and moving to MR or CT only if that modality is inconclusive.

“With CT, there will obviously be radiation exposure,” she said. “It also depends on how you do the scan.

There's a difference between lowdose CT carefully administered versus a three-phase CT scan. It depends on the technique and low-dose exposure. It's going to be a minimum of 4 to 5 rads, but there's still going to be some exposure. Also, the longer the pregnancy, the larger the patient. There are a lot of variables.”

MR may seem perfect when it comes to diagnosing pregnant women suspected of appendicitis, but it also has some pitfalls. Cost, lack of wide-spread availability during night shifts, and a shortage of radiologists who can read an MR of the appendix are some of the reasons why it is not used everywhere, Singh said.

“Attention to proper MR imaging technique and tailored protocols are essential for optimizing the effectiveness of the examination and maximizing diagnostic accuracy,” Singh said. Singh is not alone. Other physicians share his sentiments.

“Since MR is not used frequently, not everyone is comfortable reading the scan, in particular the junior residents on call,” Patel said.

MR is also a long test, and the 2007 American College of Radiology guidance document for safe MRI practices precludes physicians from using gadolinium in pregnant patients, which limits ability to detect enhancement characteristics, Patel said.

If a physician cannot detect the appendix with ultrasound, does not want to expose the patient to CT, and lacks access to an MR machine, there is one last option: surgery.

“If you have a patient come in with their right side in pain, a fever, and a high white blood cell count, there are relative benefits to doing surgery,” Javitt said.

Most patients, however, are within a reasonable range of MR, she said.

Appendicitis is a condition that requires attention. Left untreated, the risks are rupture, sepsis, and death. Javitt, however, has seen a case of appendicitis in a nonpregnant patient resolve spontaneously. “They don't all end in rupture,” she said.

While all signs seem to point to MR as the device to use when it comes to diagnosing pregnant women with suspected appendicitis, Patel, for one, remains skeptical.

“I do not think there is a large study to prove that either MR or ultrasound is better for detection of appendicitis in pregnancy, and I think use of one over the other will be dependent upon availability and the radiologist's/surgeon's preferences in the particular institution,” he said.

Articles in this issue

over 17 years ago

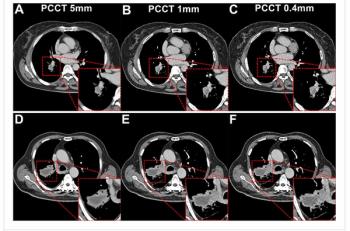

Multicenter trial confirmsvalue of coronary CT angioover 17 years ago

Siemens tweaks PET/CT T with hybrid for radiologyover 17 years ago

GE Healthcare seeks better image quality, lower doseover 17 years ago

Tech advisor CT vendors plot strategies for growthover 17 years ago

Vendors polish advanced apps with 3T platformsover 17 years ago

MRI spots anomalies in children with hearing lossover 17 years ago

CT proves clinical worth in bowel obstruction casesover 17 years ago

Strategies can limit imaging fungibilityover 17 years ago

Smart probes and biomarkers spot earliest signs of cancerover 17 years ago

MRA finds value in hydrocephalus interventionsNewsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.